More Information

Submitted: May 03, 2022 | Approved: May 16, 2022 | Published: May 17, 2022

How to cite this article: Lemperle G, Sachs C, Kassem-Trautmann K, Schröder C, Kalla J. Large odontogenic tumor in Congo. J Oral Health Craniofac Sci. 2022; 7: 001-004.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.johcs.1001036

Copyright License: © 2022 Lemperle G, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Large odontogenic tumor in Congo

Gottfried Lemperle1* , Christoph Sachs2, Katja Kassem-Trautmann3, Carsten Schröder4 and Jörg Kalla5

, Christoph Sachs2, Katja Kassem-Trautmann3, Carsten Schröder4 and Jörg Kalla5

1Plastic Surgery, Wolfsgangstr. 64, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

2Department of Plastic Surgery, Martin Luther Hospital, 14193 Berlin, Germany

3Plastic Surgery, Zug, Switzerland

4Department of Anesthesia, Hospital Horgen, Switzerland

5Schwarzwald-Baar Klinikum Institut für Pathologie, Germany

*Address for Correspondence: Gottfried Lemperle, MD, PhD, Prof Emeritus, Plastic Surgery, Wolfsgangstr. 64, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany, Email: [email protected]

An article by Baum, et al. “Unclear swelling in the region of a maxillary canine tooth” [1] caught our interest. A 14-year-old boy had developed an adenomatoid odontogenic tumor (AOT) without undergoing maxillofacial surgery. During an INTERPLAST-Germany mission [2] in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo, we operated on a young man with an advanced odontogenic tumor. Since we are confronted with fist-sized odontogenic tumors (mostly ameloblastoma of the mandible) every time we operate in Africa, where they grow out of control due to a lack of experienced surgeons, it may be of interest to our colleagues in developed countries to know which grotesque tumors are prevented by early surgery.

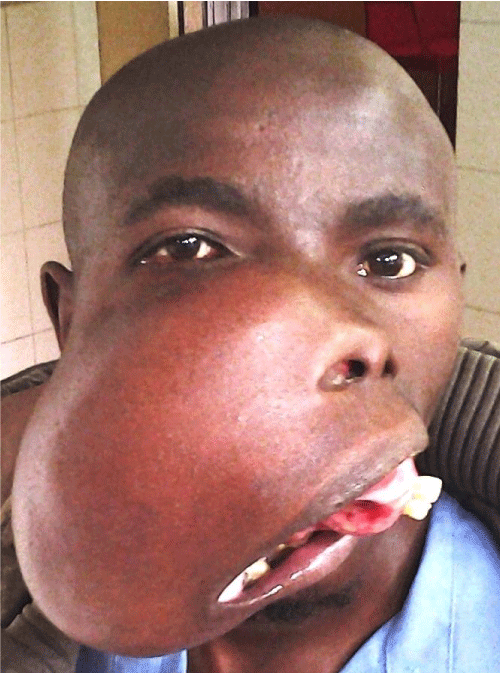

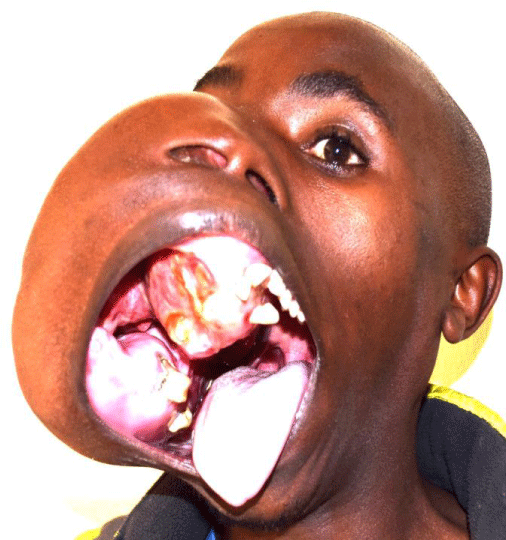

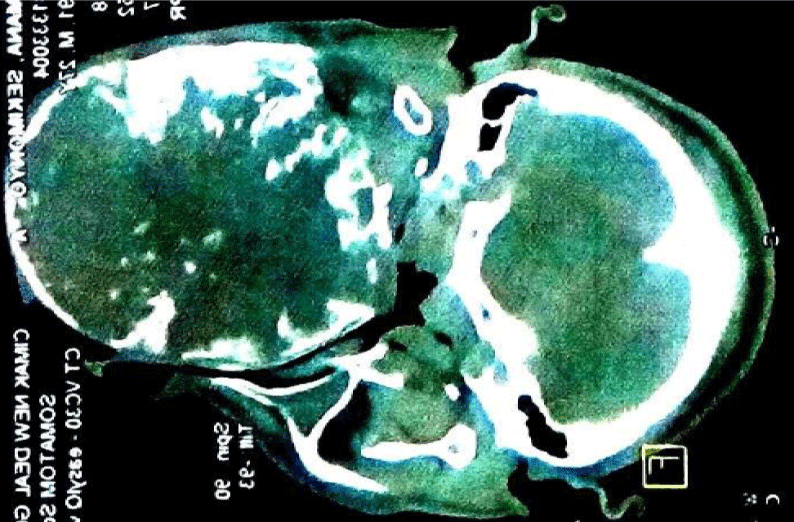

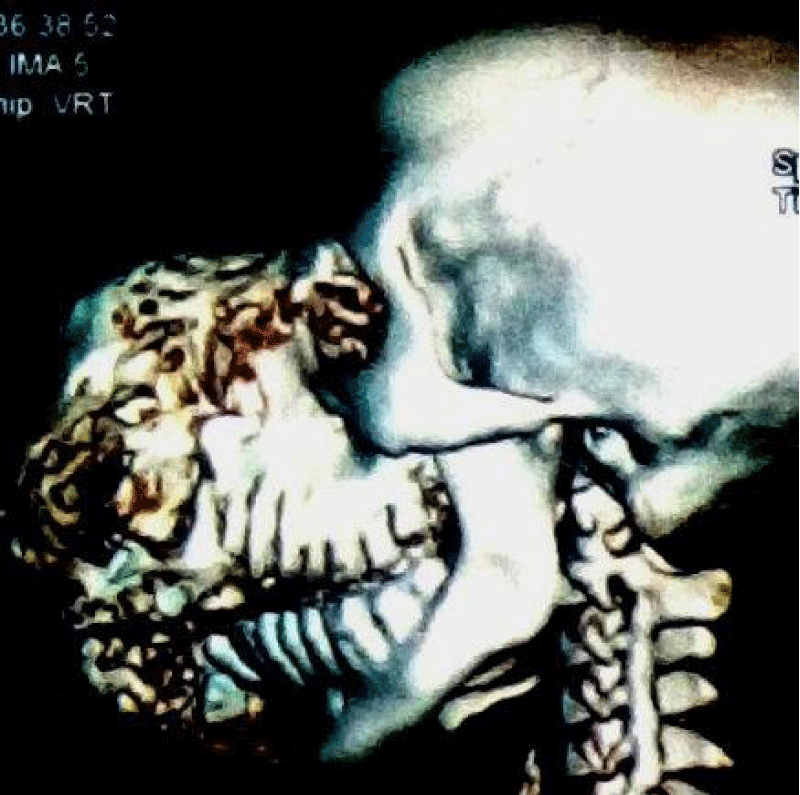

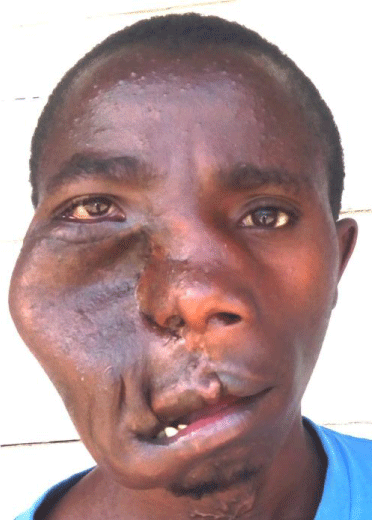

A well-developed 26-year-old male patient allegedly first noticed the tumor in his right maxilla 3 years earlier (Figures 1,2). His speech was slurred but understandable. Images from a Siemens Somatoma® in Goma, DRC (Figures 3,4), and CT showed space displacement from all sides, 3D reconstruction also showed bony structures within the tumor (Figures 5,6). Radiologists suspected ameloblastoma or bone sarcoma. Retrospectively, however, the images also revealed the classic radiographic features of odontogenic myxoma, in which the bony trabeculae intersect at right angles in a multilocular radiolucency [3].

Figure 1: Odontogenic tumor of the right maxilla in a 26-year-old male, reportedly grown within 3 years.

Figure 2: Odontogenic tumor of the right maxilla in a 26-year-old male, reportedly grown within 3 years.

Figure 3: CT in the horizontal and frontal lines shows the spatial displacement of the tumor to the left with preservation of the right temporomandibular joint.

Figure 4: CT in the horizontal and frontal lines shows the spatial displacement of the tumor to the left with preservation of the right temporomandibular joint.

Figure 5: 3D scan showing the prominent bony structures in the tumor: honeycomb-like osteolysis and fine trabeculae contained within.

Figure 6: 3D scan showing the prominent bony structures in the tumor: honeycomb-like osteolysis and fine trabeculae contained within.

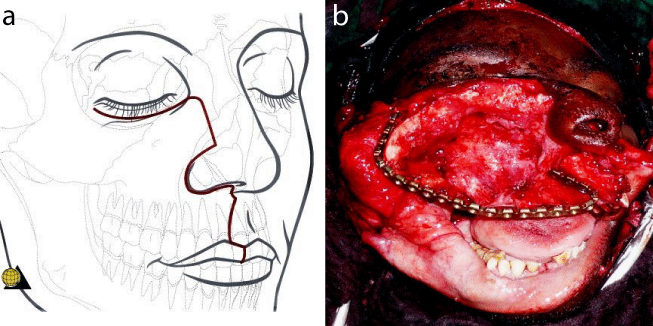

Surgery

To create an osteo-myo-cutaneous pectoralis flap to reconstruct at least some parts of the patient’s palate a tracheostomy was performed. Resection of the large tumor using an electric saw was relatively easy and caused no major blood loss. The now missing maxilla was reconstructed sub-optimally using a metal plate that was attached in an arch shape to both zygomatic bones (Figures 7). The 5th rib, raised with the vascular pedicled pectoralis flap, was internally sawed into 4 sections and arcuately fixed with screws to the metal plate, remaining surrounded by muscle tissue [4].

Figure 7: a and b. Incision to open half of the face without facial nerve disruption. The intraoperative view shows the extent of tumor resection and the plate over which the pectoralis flap will be slung to cover the plate and rib with muscle tissue.

The attached skin flap, which included the nipple region (the nipple was replanted) was sufficient for a tension-free closure of the “new” palate. An inner lining of the nasal side can often be omitted since, during the coming months, living epithelial cells sloughing off from nasal mucosa can be expected to epithelialize the “raw surface” of the airways. To allow optimal vascular connections to the muscle flap from the cranial side, the widely overstretched cheek skin was pressed onto the muscle from the outside with a bolus “pressure” dressing (Figures 8).

Figure 8: Pectoralis muscle flap, with which this skin island and part of the 5th rib are also resected and swung upwards.

The postoperative course was without complications. The local surgeon removed the bolus dressing from the cheek after 6 weeks on the condition that the upturned pectoral muscle received sufficient vessels from the well-perfused cheek skin. Another 10 days later, he transected the osteo-myo-cutaneous pectoralis flap and discarded it.

Within the first postoperative months, there was no visible recovery yet of the extremely hyperextended facial nerve branches in the right cheek (Figure 9). The patient left the hospital dissatisfied, as his speech was now even more slurred, resembling that of an untreated cleft palate patient. Unfortunately, he disappeared in the Congolese bush and never returned. When we wrote this article, we contacted “Heal Africa”, the hospital in which a free of charge MRT and CT had been done a year before surgery, but they were unable to locate the patient. Therefore, we are unable to report on his speech, the recovery of his hyperextended facial nerve, or provide a postoperative facial X-ray. Because of the frightening appearance he had been called “the Hippoman”.

Figure 9: Postoperatively, a bolus presses the right buccal skin onto the elevated pectoral muscle so that it receives its blood supply cranially in the coming weeks.

Figure 10: Final result after 3 months: At 5 months we heard that the facial paresis had recovered but the right corner of the mouth needed still a lift.

Diagnosis

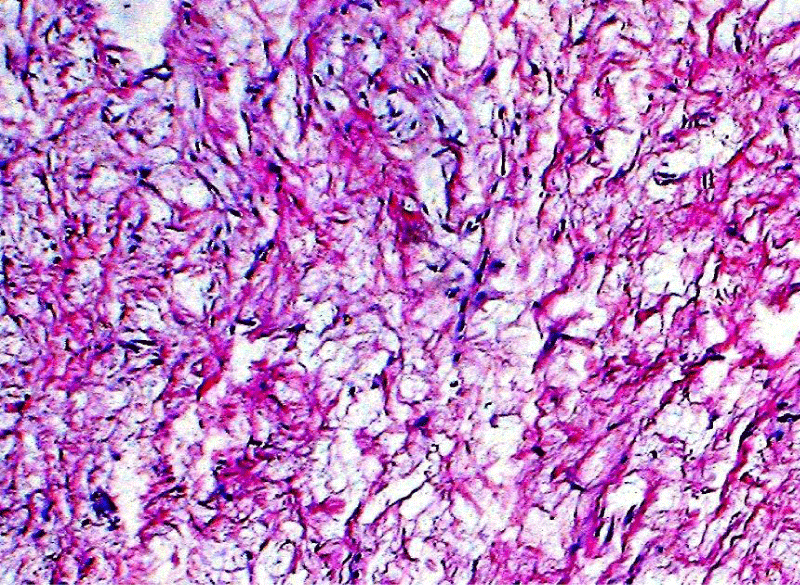

The double-fist-sized tumor had a polymorphic appearance of gelatinous soft parts and solid nodules, bone trabeculae, and hemorrhages when cut through. Since the orbital floor appeared corroded from below, a 3 x 2 x 1 cm biopsy was taken from the solid white periphery to exclude sarcoma. Understandably, the local pathologist could not detect any epithelial structures. Histologic examination in Germany revealed the following truncated findings.

“Predominantly loosened, collagen-rich tissue with optically empty spaces as in edema. The majority had low to slightly increased cellularity with low polymorphic nuclei of fibroblasts with only sporadically recognizable nucleoli (Figure 11). No mitoses. Isolated capillary proliferates. Lipomatous structures are not identifiable. Focal calcified tissue with woven bones and single indicated lamellar structures. Loose aggregates of lymphoid cells are repeatedly found, loosely intermixed with neutrophilic segmental granulocytes, as well as single erythrocyte extravasations. Single, somewhat denser bundles of collagen fibers (Figure 12)”.

Figure 11: Histopathology: loosely arranged star-shaped cells with intermingled fibrillar structures in a homogeneous mucoid ground substance of a fibromyxoma.

Figure 12: Pathological findings: the majority of low to slightly increased cellularity with low polymorphic nuclei of fibroblasts with only sporadically recognizable nucleoli. no mitoses. Fibrous portion of fibromyxoma.

Diagnosis: Depending on the clinical presentation, the findings are highly compatible with odontogenic myxoma or myxofibroma [2,3,5,6,10].

There may be a handful of maxilla-facial surgeons and plastic surgeons in the Capitals of Subsaharan Africa, who are experienced with this kind of large tumor. The pectoralis major flap was first described by Ariyan in 1979 [7]. It is a pedicled myocutaneous island flap that has become the standard for soft tissue reconstruction in head and neck surgery over the last 40 years.

In the West, the described osteo-myocutaneous pectoral flap was not considered rocket science and has largely been replaced by a free forearm or even osteo-myocutaneous scapula flap. Composite pectoral flaps [4] had been used in our Frankfurt Department of Plastic Surgery in the early 1980s to cover devastating facial defects after noma infection in children in the Subsaharan area. In comparison with local flaps, they have the advantage of not impairing the integrity of the surrounding facial skin.

A clinical diagnosis without biopsy findings from a pathologist is always a challenge for the surgeon. Surgery is necessary to prevent future suffocation. The benignity, however, is soon obvious from the clear borders of the tumor – and if there are malignancies within the tumor, they do not influence the outcome.

In 1998, at a congress in Cape Town [8], 4,384 cases of odontogenic tumors (OT) were presented from sub-Saharan Africa: 86.9% were ameloblastoma, 6.9% were keratocystic OT, and 4.9% were myxomatous OT and 1.4% showed malignant degeneration. Similar figures were published in Nigeria in 2016 [9]; preoperative biopsies were rarely present at the time of surgery and postoperative pathology was not always certain. i.e. complex OT was the second most common type of OT in this regard after ameloblastomas., (what was most common??).

An online revealed clinically similar-looking giant facial tumors from developing countries diagnosed as “craniofacial fibrous dysplasia”, which is now considered a mutation of the gene GNAS1 on chromosome 20 [10]. A myriad of subtypes of odontogenic tumors may be considered differential diagnoses [3], most often when limited biopsies are available from “mixed” tumors [11]. For the surgeon, however, this is more of a scientific dispute with little relevance to the patient or outcome.

Africa is home to 1.3 billion people today; by 2050, the number is expected to have doubled. Most of them will have to leave their countries and flee northward. Since medical care cannot keep up with this population explosion, we will be confronted with large odontogenic tumors much more frequently in Europe or our humanitarian missions. Since radical resection is the only option for almost all odontogenic tumors, a correct diagnosis by the pathologist is clinically relevant in that 1.4% of malignancies can be identified [5] for which postoperative radiation may have to be considered. Goma, a city of 2 million inhabitants, has no facilities to offer postoperative irradiation.

The surgeon must determine the benignity of a tumor based on the clinical growth and the macroscopic sectional image during surgery to initiate further controls or therapies as necessary. The suspected initial diagnosis does not always correspond to the maxim “If hooves are clattering outside, they most likely come from a horse and not a zebra” (attributed to J.F. Dieffenbach).

Take-away messageLarge irregularities after facial tumor resection are covered today with free composite flaps from the forearm or scapula. During humanitarian missions in Africa, however, there is no surgical microscope and few surgeons are used to performing anastomoses with the help of magnifying glasses. Therefore, a rather old-fashioned, but safe and reliable option is the use of a pedicled pectoralis island flap to cover most large facial defects in the reconstruction of a lost palate, and for the replacement of failed free flaps [4].

- Baum SH, Loef C, Baumhoer D, Mohr C. Unklare Schwellung im Bereich eines Oberkiefereckzahns. Ein seltener Fall. MGK-Chirurg. 2018;11:111-114.

- Charpentier A, Lemperle G. Simultaneous total upper and lower lip reconstruction during a humanitarian surgical mission to Africa. Europ J Plast Surg. 2017;40:79-82.

- Chrcanovic BR, Gomez RS. Odontogenic myxoma: An updated analysis of 1,692 cases reported in the literature. Oral Dis. 2019 Apr;25(3):676-683. doi: 10.1111/odi.12875. Epub 2018 Jun 8. PMID: 29683236.

- Meier JK, Spoerl S, Spanier G, Wunschel M, Gottsauner MJ, Schuderer J, Reichert TE, Ettl T. Alternatives to free flap surgery for maxillofacial reconstruction: focus on the submental island flap and the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. BMC Oral Health. 2021 Apr 19;21(1):198. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01563-7. PMID: 33874923; PMCID: PMC8056673.

- Bilodeau EA, Collins BM. Odontogenic Cysts and Neoplasms. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017 Mar;10(1):177-222. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2016.10.006. Epub 2016 Dec 29. PMID: 28153133.

- Correa Pontes FS, Lacerda de Souza L, Paula de Paula L, de Melo Galvão Neto E, Silva Gonçalves PF, Rebelo Pontes HA. Central odontogenic fibroma: An updated systematic review of cases reported in the literature with emphasis on recurrence influencing factors. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018 Oct;46(10):1753-1757. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2018.07.025. Epub 2018 Aug 7. PMID: 30143268.

- Ariyan S. The pectoralis major for single-stage reconstruction of the difficult wounds of the orbit and pharyngoesophagus. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983 Oct;72(4):468-77. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198310000-00008. PMID: 6611772.

- Ogundana OM, Effiom OA, Odukoya O. Pattern of distribution of odontogenic tumours in sub-Saharan Africa. Int Dent J. 2017 Oct;67(5):308-317. doi: 10.1111/idj.12301. Epub 2017 May 8. PMID: 28485021.

- Iyogun CA, Omitola OG, Ukegheson GE. Odontogenic tumors in Port Harcourt: South-South geopolitical zone of Nigeria. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2016 May-Aug;20(2):190-3. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.185934. PMID: 27601807; PMCID: PMC4989545.

- Feller L, Wood NH, Khammissa RA, Lemmer J, Raubenheimer EJ. The nature of fibrous dysplasia. Head Face Med. 2009 Nov 9;5:22. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-5-22. PMID: 19895712; PMCID: PMC2779176.

- Reichart PA, Jundt G. Benigne „gemischte“ odontogene Tumoren [Benign "mixed" odontogenic tumors]. Pathologe. 2008 May;29(3):189-98. German. doi: 10.1007/s00292-008-0996-0. Epub 2008 Mar 29. PMID: 18369623.

- Omeje KU, Amole IO, Osunde OD, Efunkoya AA. Management of Odontogenic Fibromyxoma in Pediatric Nigerian Patients: A Review of 8 Cases. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2015 Nov-Dec;5(6):461-5. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.177994. PMID: 27057387; PMCID: PMC4804660